Carnival Medea – A spectacular reinvention

by Lisa Allen-Agostini

(Originally published to the T&T Guardian 26/02/2017)

Carnival Medea: A Bacchanal, is a colourful epic that lends itself to different interpretations. As it’s based on Euripedes’ ancient Greek tragedy Medea, you could look at it as a distortion of a classic; or you could consider it an exercise in the subaltern talking to authority—the empire writes back, again. But as a piece of Caribbean theatre it stands as a work worthy of consideration in its own right.

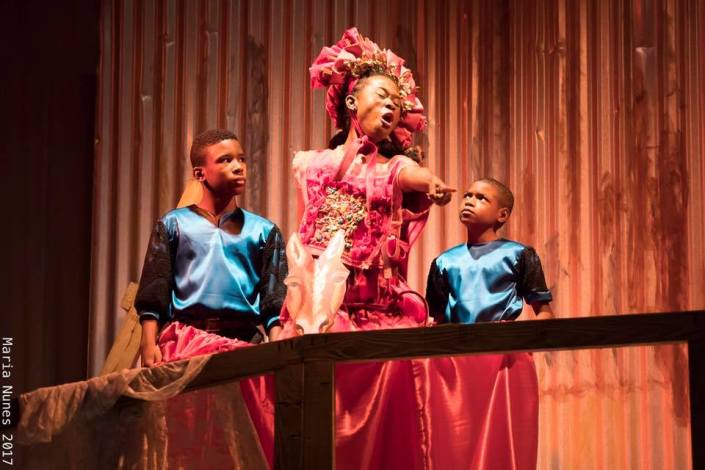

There is indeed much to consider in the work, which premièred February 9 at the Little Carib Theatre, Woodbrook. Highlighting the parallels between ancient Greek religiosity and Caribbean Orisha devotion, the play presents Medea (played by Tishana Williams) as a Grenadian obeah woman who seeks to punish her Tobagonian husband, Jason (Joseph Jomo Pierre), for his betrayal of her.

She has done everything in her considerable power to smooth his way, turning against her father and even killing her brother. For this she has been exiled from her homeland and estranged from her family.

The tabanca for this loss is as strong in its own way as her rage over Jason’s abandonment of her and their sons to marry a “red woman”, the “bourgeois” daughter of Trinidad’s Governor Creon (Kern Samuel). To punish the errant man, Medea plots to have the horner woman murdered. To the horror of the chorus and her children’s nanny (Barbadian performer Sonia Williams in a very strong performance) Medea also plots to murder her own sons.

The play was co-written by Dr Shirlene Holms and Rhoma Spencer; the latter directed the current production. You can see Spencer’s handprint on Carnival Medea; it is evocative of her work on the UWI production of Shango: Tales of the Orishas, more than a decade ago. It’s there when Shango and Ogun square off in a battle over Oshun, a scene meant to mimic the turmoil in Medea’s mind when she turns over the idea of killing her children to spite Jason. (Spencer, in a short conversation after Sunday’s show, agreed that Carnival Medea is in that sense an “extension” of the previous work.)

It becomes, too, part of a Caribbean literary tradition of works set in the urban community or barrack yard-works like Errol John’s play Moon on a Rainbow Shawl and Roger Mais’ novel Brother Man. When the Macomeres (an iteration of Euripedes’ chorus played by Cecilia Salazar, Marie Chan-Durity, Penelope Spencer and Susan Hannays Abraham) flock like parrots around the half-mad Medea there is a collective understanding that they are conscience and critic as well as comic relief.

The set carries the barrack yard theme too. White lace stretches over wooden frames made from shipping pallets to form the walls of a two-storey house. In the barrack yard there is no privacy, and so you can see the figures inside silhouetted against the lace. When Ogun (chillingly danced by Joseph Lewis last Sunday night) threateningly waves his twin knives you hear steel sharpening steel; Oshun’s sensuous undulations give many scenes a ghostly frisson.

Euripides had his Medea murder her sons. In Carnival Medea, the spurned woman rides off to Venezuela in a burrokeet chariot with her children at her side. I found it anticlimactic, but Rhoma Spencer said she had changed the ending of the work for social reasons. “I not killing no children in this 2017, not with post-partum depression and all kind of thing going on,” she said to me.

Trinidadians are sadly used to the real life spectacle of a man murdering his own children to spite his cheating wife. Here, Spencer rejects that solution and says that even at her worst excesses of grief and madness a Caribbean woman wouldn’t put God (by whatever name you call Him or Her) out of her thoughts and do that. Carnival Medea’s enduring message might have to do more with contemporary Caribbean gender politics than Greek tragedy.

Carnival Medea: A Bacchanal, was produced by Lordstreet Theatre Company. Don’t Miss the Final Run 4 -5 March at the Litle Carib Theatre